Editorial: Issue 14/ June 2024

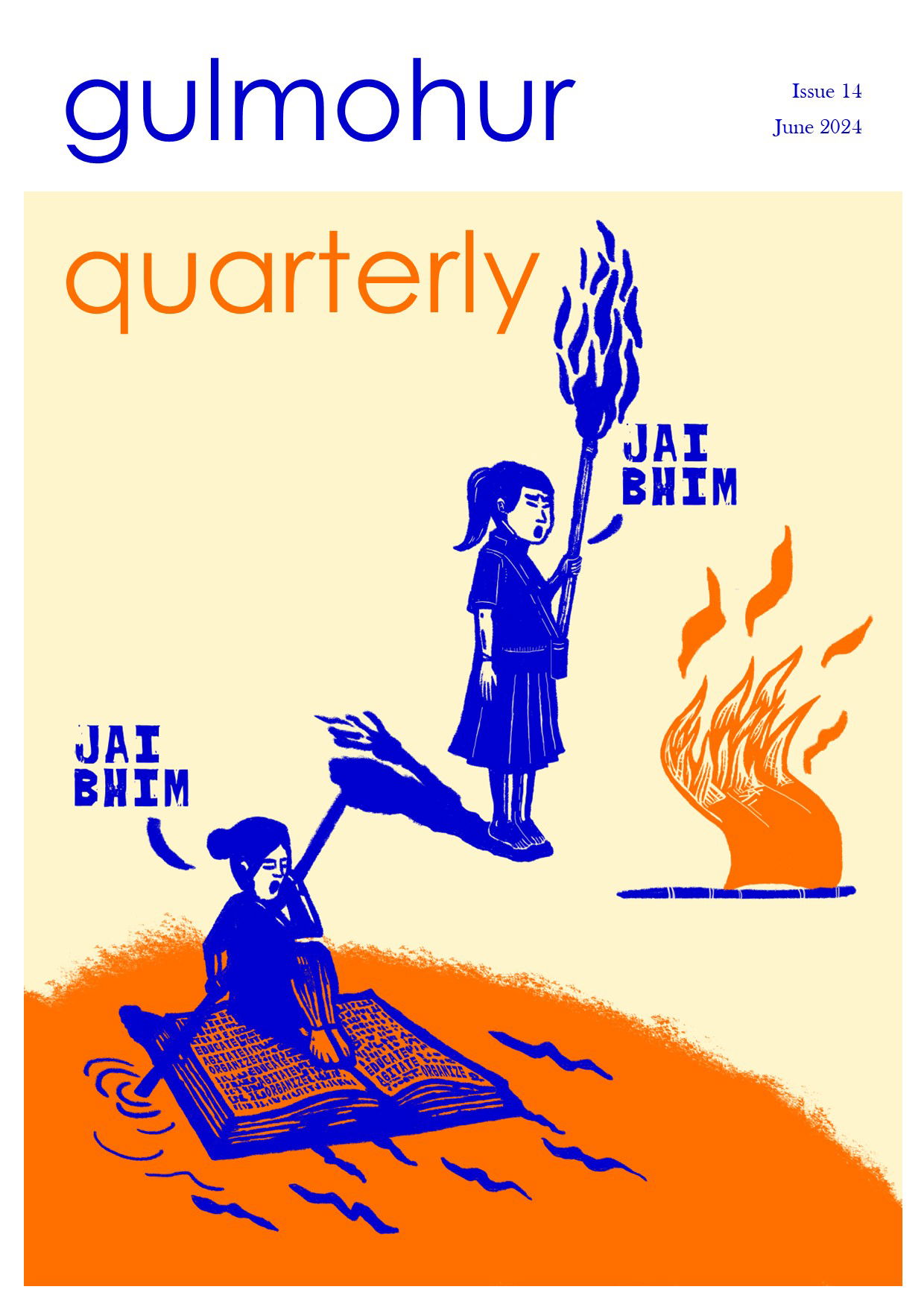

Movements have colours: blue, red, saffron. Colours of watermelon. Colours of pride. Colours can be appropriated for oppression and liberation. Colours belong not only to flags but to a lived world of assertion, dominance, and resistance. The techno-capitalist realm of commercialization renders all brands consumable, all expressions categorized and labeled, delivered to your phone-step in relentless content format, customized and palatable. Yet, we hope our attempt to draw your attention doesn’t fall into these sanitized brackets of judgment. The artist’s provocation on our cover page is a hard-hitting political statement.

The bichrome in saffron and blue articulates political anger in the face of heinous injustices and oppression. In times of neoliberal Hindutva, the revolutionary blue itself risks appropriation and co-option in the hegemonic sea of saffron. The week before the election results saw a vicious abusive attack on the digital artist Priyanka Paul, allegedly for hurting the sentiments of the ruling class. What is hurt is perhaps at once the dominant pseudo-narrative of Hindu unity and the fragile ecosystem of lies and collective delusion. Bao rightly contextualized the condemning response to the attack: “Your silence on the matter speaks volumes … Anticaste art is not simply to decorate the walls of your houses or museums but it is meant to tear down and annihilate caste from within your souls.” The charge of hurting sentiments is nonchalantly laid against the background of inhuman violence (in the forms of rapes, killings, destruction of material property, public humiliation, and the perpetual threat of existence for DBAV communities and non-Hindus) and the attacks on the artists in the form of bullying, threatening and harassment. The task of resistance art is to discomfort the viewer and to hold them accountable for their complacency in the power dynamics of oppression. The active oppressors and the silent spectators are in a profitable nexus to maintain the status quo for the privileged. The complacent on-lookers are complicit in the horror show of caste oppression and persecution of minorities. Babasaheb’s suspicion of such historically normalized oppression resulted in his radical demand for the ‘annihilation of caste.’ The proponents of reformism and cultural progressivism often miss the pragmatic-skeptical strain in Ambedkar’s ideology. His words and life stand testament to the critical examination of our social realities that demand perpetual rediscovering and reorientation.

Anand Teltumbde in Republic of Caste: Thinking Equality in the Time of Neoliberal Hindutva (2018) demonstrates that the current ruling power is seriously invested in “de-radicalising dalits” in order to be able to co-opt them and maintain its consolidation towards its long-term goal of brahminical supremacy. He argues that the ritualistic obeisance to Babasaheb is a ploy to undermine the bitter Ambedkarite discourse against Hinduism, along with mythification and crude appropriation. Contemporary India is brimming with discontent among the historically oppressed. The systemic erosion of Babasaheb’s critical legacy, its homologization into narrow agendas of ethno-nationalism and otherization of non-Hindus, and the undermining of constitutional assurance are, Teltumbde argues, a deliberate plan of the Sangh-BJP-led Hindutva’s ideological projects. To diminish all possibilities for the DBAV people to articulate their situation, such de-radicalisation becomes an all-encompassing strategy against any voice of resistance. Socially comfortable and conscientously indifferent citizens are the first to uphold the principle of non-violence; and this non-violence is stretched to the extent of being polite in thoughts, gestures, and symbolisms. Expressions of resistance must courageously challenge the symbolic expressions of hatred and discrimination, they must counter the shrinking spaces of democratic assertions, and the vocabulary and media chosen for such statements cannot always be sanitized to suit the shallow standards of the mainstream. Civility of discourse must not be an excuse to thwart subaltern interests. The very demand that resistance must obey a civil code of conduct comes from an intent of watering down the subversive capacity of self-assertion. To recall James Baldwin, “the victim who is able to articulate the situation of the victim has ceased to be a victim: he or she has become a threat.” Artists like Priyanka Paul and Bao (among many others) have not only been practicing radical resistance through their art but have also been negotiating the pedagogic discourse around anti-caste expressions, critically engaging in dialogue with a growing political community. Their “becoming a threat” is a symptom of the intolerance of majoritarianism and the vested interests of a system that severely regulates alternative worldviews and emancipatory visions; it is also a consequence of their refusal to be policed and have terms dictated. Such resistance comes at a serious cost of personal well-being and the precariousness of the condition is magnified in the absence of an actively vocal and supportive community. An artist armed with a somewhat democratic platform, digital medium, political learning, and scathing wit undoes the dreams of dictators. Such an artist cracks down on fake news, myths, historical lies and clears up space for educated responses to contemporary political situations.

The ultimate de-radicalized subject is the one who fails to articulate their situation of powerlessness, perhaps failing even to comprehend the paradigm of their social agency. Such a subject is desirable by most political outfits as they can be fashioned into bearers of any arbitrary socio-cultural aspiration, and can be directed towards a sense of fulfillment in any obtuse, absurd political enterprise. As the upward mobility of a few among the historically oppressed becomes detached from their political understanding and orientation, we obtain a system where the past retains its oppressive grip against the progress of the present. Those who suffer the most from such oppression are inevitably in a marginal position and are constantly denied opportunities for betterment and voices of representation. The evils of caste society flourish unabatedly even within the post-Independence realm of constitutional law. The ever-deepening roots of casteism in the Indian soil are evidence of the “brahminical cunning” that keeps up the pretense of liberal egalitarianism and perpetuates the age-old order of subjugation in contemporary forms. “An Ambedkarism channeled into slogans, poetry, flags, banners, Buddha viharas, congregations–the entire arsenal of symbolic displays–is simply an ecstatic mood without ideological content, and can be harnessed to various and conflicting ends” (Teltumbde, 2018). The ends to which the ruling dispensation (and suspiciously enough the opposition at times) employs such symbolisms in its own interpretation have often successfully modulated the agitation of various people’s struggles. To escape the fate of marginalization and oblivion in a politics of majoritarian set-up, the artist seeks to retrieve the symbols of resistance and give them the edge for their contextual statement. Thus, the torch becomes an emblem of fiery comportment and the book becomes a means of ideological grounding, helping one keep afloat in times of great despondency.

As the election results have slowed down the onward march of an authoritarian regime, we must strive and secure the collective agendas of social justice. We must recover the voices of resistance and organize toward a future that must deal with a lot more than can be anticipated: democratic backsliding, capitalist inequality, ecological destruction, technological dominance, and humanitarian crises. As the leaders of the opposition wave a red copy of the constitution and chant Jai Bhim, they must also now give voice to the weakest members of the society. We must speak up for the vulnerable among us, we must stop the demonization of Muslims and DBAV people, defend our public intellectuals, free the political prisoners, target the capitalist destruction of forests and livelihoods, sustain the dreams of gender justice, and rage against genocide and Western imperialism.

*

The current issue excels in presenting valuable translations from Indian languages alongside original writings. Two stories from Hindi take us to a bygone era: one introduces us to the character of a hangman (jallad) and his tender affection for a young boy; the other takes us to the partition riots in Calcutta and reflects on the cruel terms of public and divine justice. Another translated story from Telugu ponders upon the question of communal harmony and gives a glimpse into the world of those common people who see significations take on different meanings. The author sums up our situation in a somewhat tragicomic imagery: as we hop onto a bicycle backseat and hear the threatening rumbling of the chain, we “start believing that it won’t break;” thus our bicycle of co-existence wheels forward. The poets in this issue raise their voices against the horrors in Palestine and lament the fate of humanity, they weep at the death of children and curse a world that carries forth. A Hindi poet acridly concludes, “Hence, beneath the seemingly complete poem, / There lies an even larger graveyard / The bigger the graveyard, / The greater the poet and the nation.” There are poems of love, separation, longing, heartbreak; and also of the mundane ways in which we become accustomed to love, and get saturated in the other’s company. Some of the poems dwell on women’s encounters in a man’s world, of navigating public spaces and gazing in the mirror for a form of desirability, articulating the murderous frustration and coping with everyday exhaustion. A set of poetry translations from Odia captures the anxiety of the everyday in surprisingly short verses. There are poems on war, on civilization, and on what it means to be human. Another set of songs by a bhakti poet rendered in elegant translation brings to us the ordinary expression of divine, coupled with a dream of socio-spiritual emancipation. The essays in this issue devote themselves to criticizing socio-cultural dominance through various modes. In thinking through a book of translated classical Tamil poetry, an essayist reflects on her own position of privilege and critical agency. Another takes up the discussion of a film on Hindustani classical music with the filmmaker and attempts to see through the material and mytho-historical constructions of a musical world. A simple essay by a Hindi writer takes up musing on muskmelons and afternoons. Finally, we have a bold and urgent appeal from the artist of the cover art who draws our attention to the casteist business of visual design, politics, and culture.

*

gulmohur stands in solidarity with the jailed activists and intellectuals of the Bhima Koregaon case; the victims of communal hatred and of state violence; the victims of caste and gender violence; the victims of fundamentalist oppression anywhere in the world; and with all those who dissent in the spirit of democracy to safeguard our ever-diminishing freedoms. We stand for the liberation of Palestine.

*

We have successfully started working with the second cohort of gulmohur Translation Collective; we thank the members of Hindi groups for assisting us with copy editing the translation entries published in this issue. We would like to express our profound thankfulness to our readers and well-wishers everywhere. We are immensely grateful to all our friends (on and off social media) who have helped us reach out. We also thank our contributors for trusting us with their submissions.

*

We hope you enjoy reading Issue 14 of the quarterly. Happy Pride! Long live resistance!

Editors

gulmohur

June 2024