Literary Lessons with Nazim Hikmet/ Abhimanyu Acharya/ Issue 07 & 08

The proliferation of the Master of Fine Arts (MFA) in creative writing programs across North America and Europe in the past few years shows the growing importance of formal training in writing within the publishing industry. Some of my friends who were against an MFA degree do not consider it such a bad idea anymore. Considered earlier an offspring of literary studies that did not guarantee a job the way, say, a degree in English literature did, the MFA program has come a long way in establishing itself as a formidable step toward a promising career path in writing and publishing. One can even argue that the MFA degree has become a short but definitive way for agents and publishers to separate the chaff from the wheat such that for writers, especially in North America, an eventual MFA degree has become inevitable. While it is a matter of great fortune to be able to enroll in an MFA program and reap the benefits of professional training, fellowships, networking, and regular writing assignments, not all of us are lucky enough to do that. Most of us do not have the means, the right age, the financial condition, or the right language to undertake an MFA degree. In such a scenario, to come across a book such as In Jail with Nazim Hikmet (2010), written by Orhan Kemal (1914 -1970) is nothing short of fresh air.

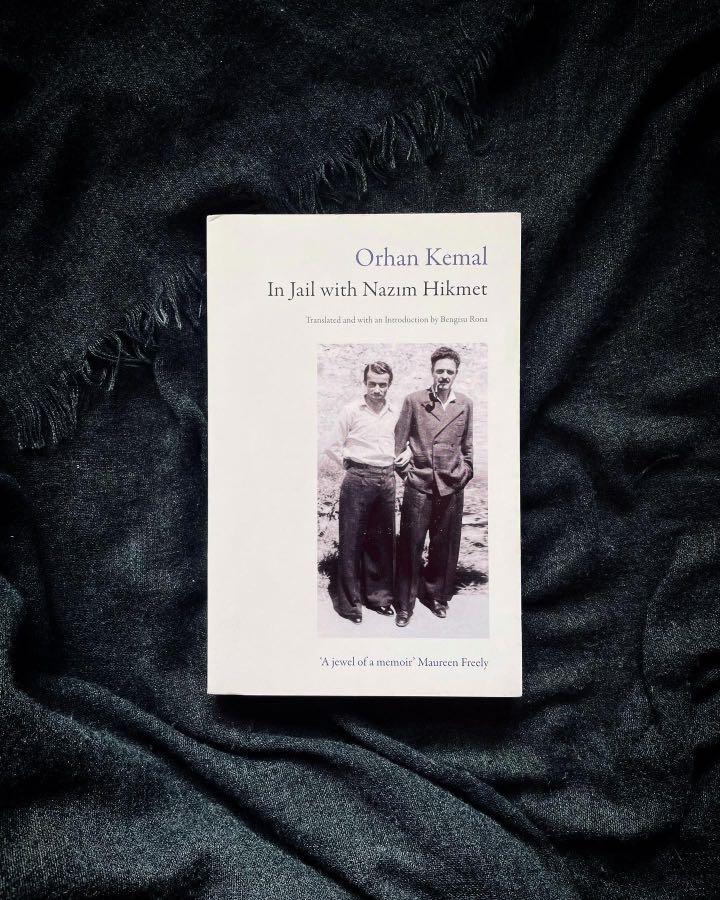

The book recounts three and half years that Orhan Kemal, arguably the greatest prose writer in Turkish literature, spent in Jail with Nazim Hikmet (1902-1963), his literary mentor and the national poet of Turkey, equaled in caliber only by the likes of Neruda, Faiz and Mahmoud Darwish. The book is both a memoir and a tender, endearing portrait of a teacher. Written originally in Turkish in 1947 and published in 1965, the book appeared in English in 2010 and has been introduced and translated by Bengisu Rona. The English edition also contains diary entries of Kemal from his prison days as well as some letters exchanged between Hikmet and Kemal once the latter was released. Together, they provide a satisfying glimpse into the literary as well as the political climate of Turkey during the second world war while simultaneously documenting the artistic training that Kemal received in the most unusual of places: a prison.

Orhan Kemal was twenty-four when he was sentenced to prison for five years for inciting mutiny in the military and for producing propaganda for a foreign state. These charges were laid specifically because Kemal was found reading books of Maxim Gorky and Nazim Hikmet and was suspected to be a communist by Turkish authorities. Nazim Hikmet, who was already a celebrated poet in Turkey, had made his communist alliances clear and, according to Bengisu Rona, was seen as a much bigger threat by the Turkish authorities and was sentenced to prison for twenty-eight years. Chance brought them together in Bursa prison in 1940, and thus began a relationship that shaped Kemal from a budding poet to one of the most promising writers of his generation. Seeing his potential, Nazim Hikmet, the ever-generous teacher, took Kemal under his wing and gave personal attention to his literary education. Sharing a prison cell with Nazim Hikmet taught Kemal many things. It is easy to lose track of the literary lessons Kemal learnt from Hikmet as they are buried in the book under anecdotes, memories, opinions, and incidents. Here, I distill some of these vital lessons about literary art.

(1) The first lesson that Nazim Hikmet teaches Kemal is to recognize one’s genre. When he met Nazim, Orhan Kemal fancied himself a poet and indulged in writing avant-garde poetry. Dismissing Kemal’s poems as ‘Mumbo-Jumbo’, Nazim advises him to focus his attention on prose since his prose was fresh, without external influences, and came naturally to him. The advice worked so well that Kemal went on to write twenty-eight novels, fourteen collections of short stories as well as several plays and film scripts in his lifetime, thus firmly cementing his place in the canon of Turkish literature.

(2) Then came recognizing and understanding the structure of a literary piece. As exercises, Nazim provided several isolated lines to Kemal and his other friends in prison and asked them to arrange the lines so that a beautiful poem emerges from them. It was one of these exercises, disguised as a test, that prompted Nazim to take Kemal under his wing since he managed to arrange the lines in the best possible way. These early lessons in understanding structure and sentence arrangement proved vital in Kemal’s training.

(3) Nazim also emphasized the importance of knowing a different language. One of the first questions he asks Kemal is, “How is your French?” Realizing that Kemal’s French needed polish, he teaches him the language through regular lessons. The training in French became so rigorous and taxing that at some point Kemal was on the verge of giving it up altogether. One can understand the reason behind such an activity: for a writer, it is important to learn a new language to expand their reading horizons, to be able to look at a language from a distance and to feel its texture not as an insider but as an outsider. What better way to understand one’s tool than this?

(4) What is true of languages is also true of other art forms. One of the things Kemal learned from Nazim Hikmet is the way other arts can influence and affect writing. Throughout his time in prison, Kemal saw Hikmet shifting between writing and painting. When he was inspired, he would write, and when he was not in the mood to write, he would make portraits of other inmates in prison. While making their portraits, Hikmet would ask the inmates to share their personal stories. Many of these stories became a basis for the visually evocative epic poem Hikmet composed in prison called Human Landscapes from my country, a modern classic of Turkish Literature.

(5) Hikmet provides meticulous feedback on Kemal’s stories and even goes as deep as explaining, through concrete examples, how punctuations can ruin sentence structures. Hikmet, a champion of simple and accessible prose, advises Kemal in one of his letters to use sentences that make sense without the usage of punctuation. According to Hikmet, ‘Sentences that cannot be understood, or can only be understood with difficulty without punctuation marks, are sentences which have been structured wrongly.’ Hikmet is also suspect of similes and believes that two or more similes in a sentence would corrupt each other and kill each other’s effect.

(6) Amid the second world war, when feelings of hopelessness and vanity were pervasive, Hikmet advises Kemal not to lose hope and to not produce works that do not champion hope. Hikmet believed that reality, however harsh and sad, should be portrayed in a way that the hope for a better future for humanity remains alive. Writers who fail to do that, according to Hikmet, are like doctors who believe that men’s fight against disease is in vain. When literary trends in Europe were inclining towards existentialism and the portrayal of absurdist meaninglessness, Hikmet advises Kemal to go against the trend. One can debate the merits of any literary movement. The takeaway here is that one need not be afraid to carve a different trail. If one believes in a particular mode of expression, one should go for it, irrespective of whether it fits the current trends.

(7) Orhan Kemal confesses that Nazim Hikmet played the most important role in his development as a writer not because of all the things about the craft that he learnt from him, but because of the fundamental truth about art that Nazim taught him. Kemal makes a useful distinction between ‘seeing’ and ‘looking’. ‘Seeing’ entails seeing the world as it is, how most people see it. ‘Looking’ entailed seeing the world within a certain methodical framework. In other words, seeing the world from a certain perspective. That is what, for Kemal, makes art. Not vision, but perspective.

(8) Nazim Hikmet does not fail to tell Kemal what every writer needs to hear at least twice a day. He tells him to write regularly and consistently and as much as possible, even at a personal cost. While this may sound like the most banal of advices, it is also what most writers, especially new ones, fail to follow. It demands rigorous discipline and hard work. Nobody can teach that, every writer must push themselves to do it, one way or the other.

What is revealed through Kemal’s memoir is not just the generosity of the teacher to teach, but also the willingness and dedication of the student to learn. Kemal learns as much from observing Hikmet and other prisoners around him as he does from his lessons. Prison introduces him to shades of life that one rarely finds elsewhere. Perhaps the greatest argument the book makes is against the places we collectively allot to training. It tells us that literary training does not require an MFA degree from a university. Training happens not through institutions, but through teachers. With the right teacher, training can occur even in the cruelest of prisons, amid isolation and violence, between thieves and killers.

Abhimanyu Acharya is a short-story writer, playwright, reviewer and translator. He writes and translates between English, Gujarati and Hindi. He has been awarded the Sahitya Akademi Yuva Puraskar for his collection of short stories and has also been long-listed twice for Toto Funds, the arts award for creative writing in English. His works have been published in places such as Out of Print, Indian Literature, Hakara, Chaicopy, Karvaan India and Reading Room. He is currently undertaking his doctoral studies in Ontario, Canada.