No Home For Women/ Semanti Debray/ Issue 06

The lives of a vast majority of Indian women hinge upon maps traced by inexorable relocations. They are born within the space of the patrilocal home; and yet, it is time and again proclaimed that this is not her home – a principle sung unceasingly till it has been proverbialized into an elementary gospel that make up the marrow of Indian family and society. The heteropatriarchal system owes its durability to this constructed fundamental truth – it thrives upon the compulsory and pre-ordained relocation of women. Denial of a woman’s ‘own’ home becomes an essential originary principle to justify her simultaneous confinement within the very homes she cannot own. The patrilocal centre of home, which remains unchanged for men regardless of marriage, shifts for women with every shift of the ownership of their bodies – father to husband, husband to son. The institution of family and home is often very unhomely for women, who hail from heterogeneous spaces and backgrounds they have left behind.

This project seeks to examine the map of often painful hybridity etched by women’s stipulated pattern of relocations and dislocations. For this purpose, I shall utilise material objects belonging to and created by women within my family, along with related anecdotes from them. While the accompanying passages are primarily descriptions of the objects on display and related skill formation, they also delve into very personal narratives from the lives of the women themselves, to illustrate the full impact of non-belongingness. The installation would attempt to create a tapestry of the hybrid identities formed in this process of migration and resettlement, through an examination of material culture of women’s non-homes.

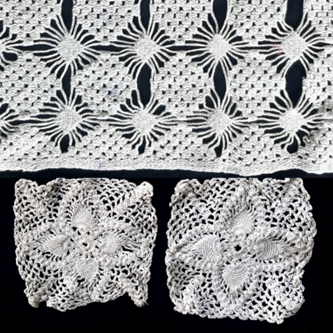

Fragments of a crochet table cover, incomplete crochet radio cover

Pieces crocheted by Minati Dey (Sur), my grandmother, roughly during the early 1970s. The bigger piece was used as a radio cover, while the smaller pieces were intended to be sewn together to create a larger table cover.

Pieces crocheted by Minati Dey (Sur), my grandmother, roughly during the early 1970s. The bigger piece was used as a radio cover, while the smaller pieces were intended to be sewn together to create a larger table cover.

While marriage is usually understood as the primary cause of migration for women, from one home to another, for Minati Dey (Sur), my grandmother, relocations began long before her marriage. Her parents’ attention divided between eleven siblings of various ages, some of them would often have to spend some periods of time with relatives in different locations. Her skills in knitting, crocheting and sewing too, were picked up in patches, from several different homes. She claims to have learnt basic sewing from her watching her mother, who in turn was known for her fabulously embroidered kanthas (light variety of quilt created by sewing old pieces of saree or cloth together, in layers). Threads were cautiously extracted from old linings (paar) of saree, to be used for colourful embroidery on kaanthas.

The art of crocheting and knitting was picked up in a different home – that of an aunt who lived nearby. Minati chuckles as she recalls learning by practicing on cycle spokes and broom sticks, as knitting needles. She went on to create copious amounts of wool garments for relatives throughout her life. Soma recalls how Minati would often observe strangers walking past their home, wearing sweaters with unique new patterns, and recreate those with perfect ease.

Tablecloth created by extracting threads from the primary fabric itself to create a pattern.

Although she picked up these skills before marriage, as a girl, Minati only found the time to engage in knitting, crocheting and sewing after her marriage. This particular cotton tablecloth was created using a rather rare and innovative technique, picked up from a neighbour, that specifically requires careful hand sewing. The cloth is first punctured using thicker crochet needles, loosening, but not damaging the individual threads. The very same threads are then sewed back to bind the punctured ends of the cloth, creating a pattern. This technique is particularly notable in that it has no requirement for extra threads, and utilises the threads that constitute the primary fabric itself.

Threadwork done on table cloth using threads extracted from primary fabric

Minati was introduced to this technique as a married woman, living in Dumdum Cantonment, Kolkata. Although her paternal home was in Chittaranjan, a small town in Bardhaman, West Bengal, Minati migrated away from her home well before marriage to pursue higher studies. This was no small feat for a woman from a fairly conservative lower middle-class family overburdened with children. Her education beyond fifth standard in school had been completed on sheer grit and determination— with no books, no chappals, insufficient stationery, and the ultimatum that a single failure would be the end of school, Minati persisted through school. She recalls taking notes with a pencil first, and then writing on top of the same with a pen, to fit two sets of notes into the same page. Sending a woman out of her maternal home for college education is a rare phenomenon even today; in the 1960s, Minati starved herself for three days till her father was compelled to let his daughter pursue a degree in History, away from Chittaranjan, in Kolkata.

Degree interrupted momentarily by a circumstantially unavoidable marriage mired in scandal, Minati relocated once again into her marital home away from Kolkata, in Gobardanga, from where she completed her Bachelors. “I married your grandfather with the help of friends”, Minati laughs cheekily, as she recalls a rather unconventional marriage, still largely a taboo. Acceptance, or the lack of it, into her marital home was uneasy and painful. Entirely unskilled in cooking till then, Minati recalls struggling to pick up cooking in her new “home”, where her mother-in-law, a remarkable woman herself, refused to teach her any. In unhomely homes, women are hungry for scraps of affection and guidance, which arrive from the most unlikely places – a brilliant cook later in her life, Minati picked up most recipes and spice mix formulae from a doting grand aunt-in-law in the Gobardanga house. “Widowed at the age of five, and sent away permanently from her own father’s house, she was bent over by the time I met her”, Minati recalls.

We are thus, looking at trans-generational threads of alienation and marginalisation of women within the space of the home. Repeated relocation due to the patrilineal and patrilocal kinship structure becomes an isolationary tactic, that prevents women from accumulating social capital through solidarity and community, by denying them the stability of home ownership and fixed lineage. However, even within the space of alien households, solidarities are built between heterogenous women coming from disparate cultures and families. Thereby, learning comes through hybrid epistemologies passed down and inherited in odd ways, from odd sources.

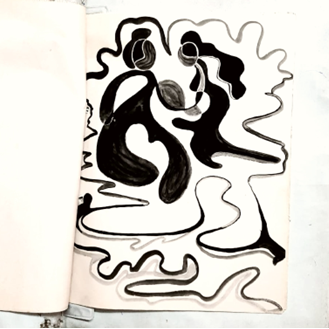

Some pages from Soma Debray (Dey)’s sketchbook

While certain skills, like cooking and sewing, are hyperlegitimized as feminine crafts, absolutely necessary to run a household, others are perceived as excessive and unnecessary. Soma Debray (Dey), my mother, never received formal training in art. She however received steady encouragement from her mother Minati, who advised her to start using references to perfect sketches. These sketchbook pages date from her high school and college days.

In the process of migration from paternal to marital home, it is demanded that a woman must sacrifice the practice of excessive, self-serving, unnecessary hobbies. It is often not a question of lack of time, due to being occupied with housework, employment or children. Rather, it is seen as natural that with each migration and dislocation, women must leave a certain part of them behind to embody a new role.

Young, unmarried women are often encouraged to take up hobbies like theatre, art and dance; however, when they leave the space of the maternal home, relocating to a different temporal and geographical space of marital home and life, it is expected that these hobbies are abandoned. Of course, they cannot be entirely abandoned, and result in bitter and uncomfortable remnants, hidden and forgotten legacies. Thereby, we repeatedly see how material objects belonging to and created by women, are not only carried from one home to the next, but also perceived differently in each new space.

Post-marriage, Soma had to eventually give up art, and eventually destroyed most of her old sketchbooks in rage. However, some survived like the one in these photographs, and continue to disrupt the space and culture of her marital home. Art was not among the hobbies appreciated and practised in her new home, till her children came along. Her sketchbooks were for long, an oddity, and continue to be; for even though children may be trained in art, for their mother to train herself in it is considered self-indulgent.

This kaantha was sewed and embroidered on by Soma Debray (Dey), for her infant daughter in the year 2001.

This kaantha was sewed and embroidered on by Soma Debray (Dey), for her infant daughter in the year 2001.

Although the patrilocal marital home strives to obliterate unbecoming skills and cleanse wives and mothers of disruptive individualities, it is certainly not a unidirectional and linear process. The space of the patrilocal home itself undergoes conflictual or favourable hybridisation by the lived realities of multiple women from heterogenous backgrounds and histories. While on certain fronts, this hybridisation is welcomed, it engenders conflict and friction on others. Introducing new knowledge of embroidery techniques, patterns and products to the fold of the patrilocal marital home is traditionally welcomed and its bringer is appreciated for her skills and know-how. New dishes are welcomed, selectively however: pickles and sweetmeats are ubiquitously appreciated, whereas daily diet often becomes a ground for conflict and alienation.

Close-up of the kaantha

Close-up of the kaantha

Soma’s sketches and watercolours were symbols of disruptive heterogeneity and defiance in her marital home. However, a reconfiguration of her art into embroidery, to create colourful kaanthas like those by her maternal grandmother, was seen as entirely appropriate and dutiful as a new mother. Women carry fragments of their old self to new spaces repeatedly, resulting in trans-generational consequences and legacies – a wealth and inheritance of scraps.

Despite the systemic normalisation of women’s non-belongingness, our quotidian culture often betrays an acute awareness of the aforementioned body of ambiguous inheritance – the proverbial texture of our languages overflows with tales of the domestic woman’s wisdom and grit, resourcefulness and suffering. The profound cultural impact of these informal epistemologies even extends to the imaginary of the public sphere; simultaneously, women’s histories are rarely recognised and honoured as the root of the same. The corpus of women’s creative labour exists and flourishes, sometimes in conformity, and often in conflict with neat categorisations of the spaces of heteropatriarchal confinement. As women find themselves repeatedly compelled to relinquish skills, hobbies, and talents constitutive of their very identities, the space of the patrilocal home itself becomes diffuse and unsettled, on its encounter with their polyphonous legacies of non-belongingness.

Semanti Debray is a graduate student at Centre for English Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University. She is a freelance artist and her artwork is available for viewing and sale on her Instagram page @_splotches.