In Their Name/ Tasneem Khan/ Issue 17

Haji Dada read till his stories turned mad. Till they possessed every inch of his being. They seeped through his flickering kerosene lamp, playing tricks on the walls. They followed him like a shadow, they crowded his room. Sometimes he would find them lazing on the chair, smoking his beedi. Sometimes they would loom around his bed. In the scorching heat of April, he would watch them dozing off in the chaupaar, lulled by the blissful breeze of the gulmohar tree across the window. Sometimes they tricked him, sometimes they haunted him. Sometimes he yielded to them, sometimes he reconciled with them.

But Haji Dada is not someone you might think of him to be. He was no scholar with rimmed glasses hanging loose on his nose, or a writer who meets an unfortunate end. His room had a few things; a bed, a table, a bakas with books filled to the brim. He could not quote Shakespeare, he might have never heard the name even. But I know he breathed the word of Faiz. Haji Dada was an old man, with saggy skin and an almost grayish beard. He mostly looked shrivelled and consumed. He spoke crude Awadhi, but he lived in Urdu, in its crooked, coastal geography. As Darwish would say, he poured himself into the letter noon (ن), until it couldn’t contain him, until he overflowed, until he gushed wild like a river under the spell of a nasty storm, until he became everything, and then nothing.

His room is what dominates my memory of him. Its smell always lingered. A strange mix of old furniture, his packets of medicine and the cloying heaviness of damp air. People say excess reading took a toll on his eyesight. With a deteriorating vision, hemight have taken to imagination, which wavered to the edge of hallucination. Maybe Haji Dada would re-tell himself stories he could no longer read. Maybe he started believing in them with the same madness of a Farhad carving out a river of milkthrough a mountain. Indeed, to hold on to a story, you simply have to believe in its truth.

But my concern here is the crossroad where others like Haji Dada stand. It is that my village is a tiny speck on India’s magnanimous map. No information about it is traceable, apart from an archaic census statistics. All that it ever had is one mosque,one communal graveyard and several mango baghs. This is Haji Dada’s crossroad. Far removed from the abundant world of the urban, intellectual reader; it is the liminal space a rural, ‘semi-literate’ is subjected to.

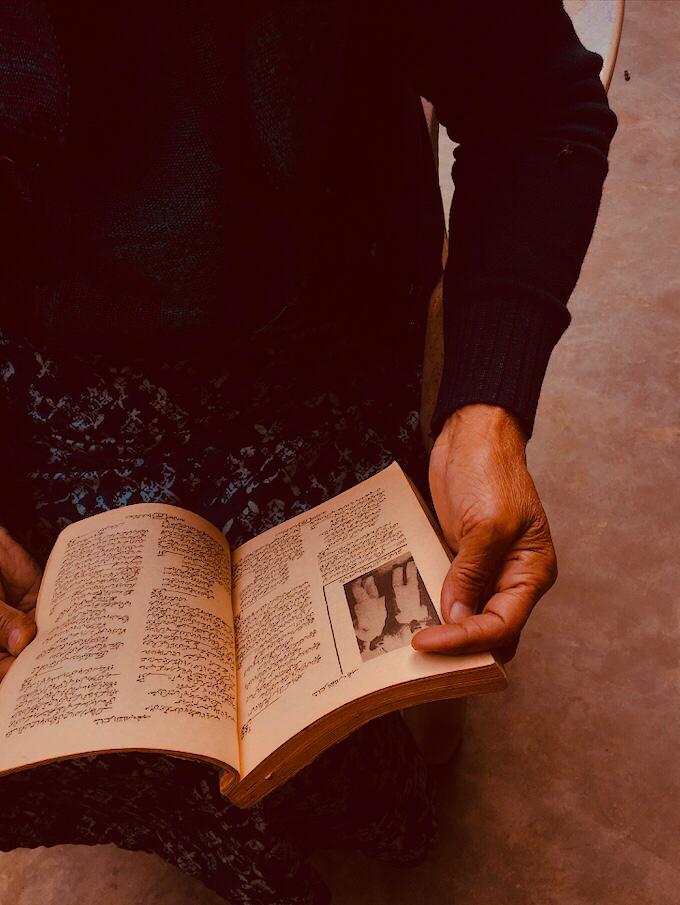

This is the world of Haji Dada. This is the world of my grandfather, Maulvi Anis Ahmad Khan. A man who died with books kept by his side. Who quoted Haider Ali Aatish, Mirza Ghalib, and Allama Iqbal even though old age nibbled on his memory. ‘They are all I have,’ he would say, while holding the torn, dust ridden books he stacked for a second reading.

Yet, for all his devotion to literature, outside his liminal world, in front of a well spoken, urban intellectual, in his ash white lungi and Awadhi-laden Urdu, he will always be an uncivil peasant, he wouldn’t speak of his books, perhaps he wouldn’t speak at all, his identity would be a puzzle piece of assumptions and before he’d realize, he would already be ‘spoken for’ by a benevolent narrator.

The more I moved ahead in life and entered new spaces with ‘well-read’ people and connoisseurs of ‘serious literature’, the more I thought of Haji Dada and Maulvi Anis, the readers. A part of them remained in me, and it felt alienated on their behalf, it raged, cursed and then naturally dissolved into obscurity.

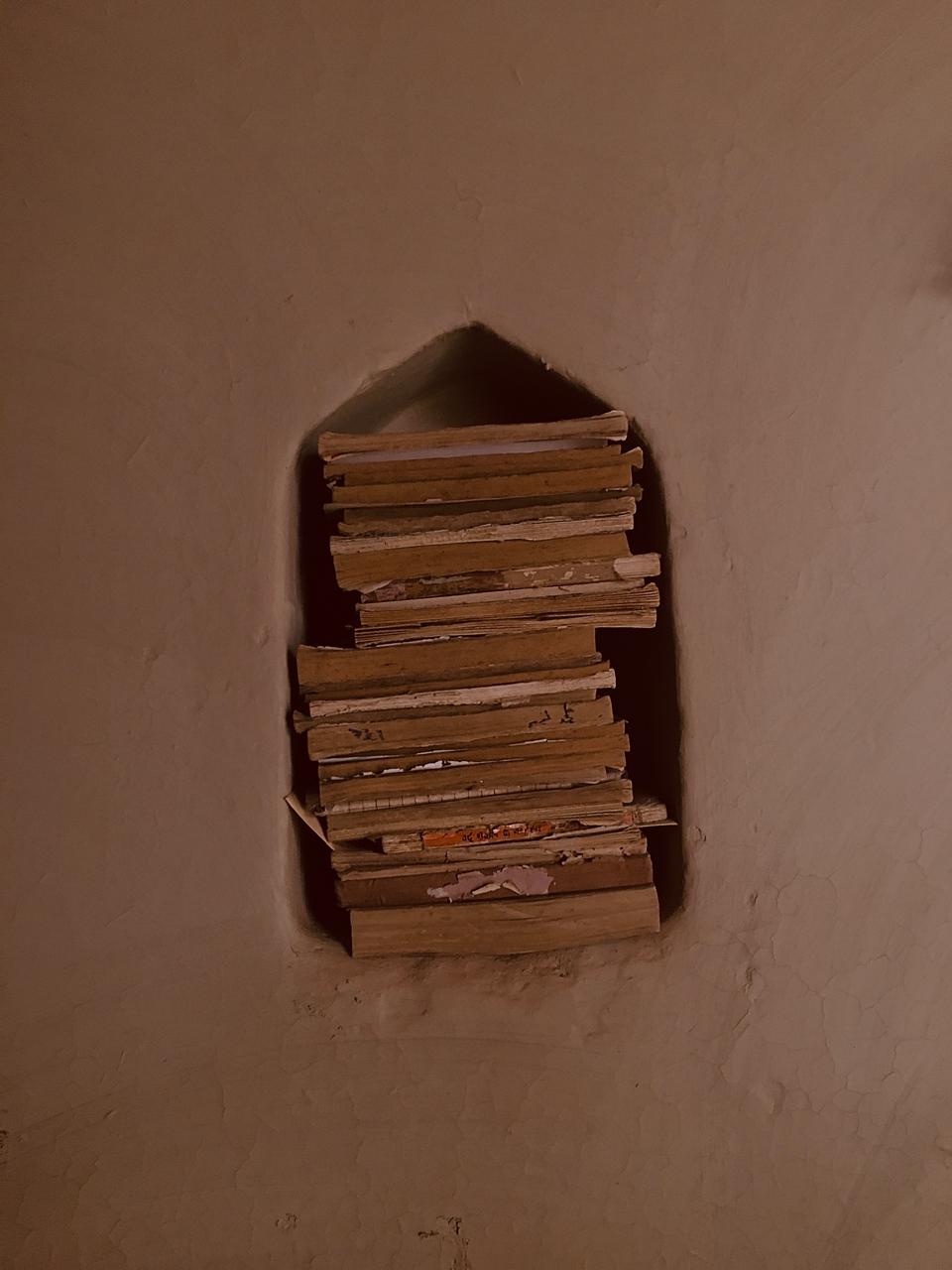

Often, I think of this quote by Stephen Jay Gould, ‘I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein’s brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.’ Throughout his life, Dada worked multiple jobs. He was the village school’s headmaster. A farmer. Managed a brickfield. His life went by in creating something for his children, he left us lush rice and peppermint fields. Mango baghs. A house. And his collection of books that rest untouched by anglicised hands.

But even in the midst of this chaos, of life pulling him in all directions, he read. I could not understand it. I come from a space where books, reading, literature has been commercialised and romanticised to the point that it has become some sort of a‘thing.’ And here was Maulvi Anis, re-reading his old books through an afternoon in January, simply because. Sometimes I wonder how different his life would have been if he had a father who nurtured his interests, like he did for his sons. Or if he was from a place which wasn’t a tiny speck. Would he have been a professor? A poet? An editor? Who knows. Truth is, he died a farmer.

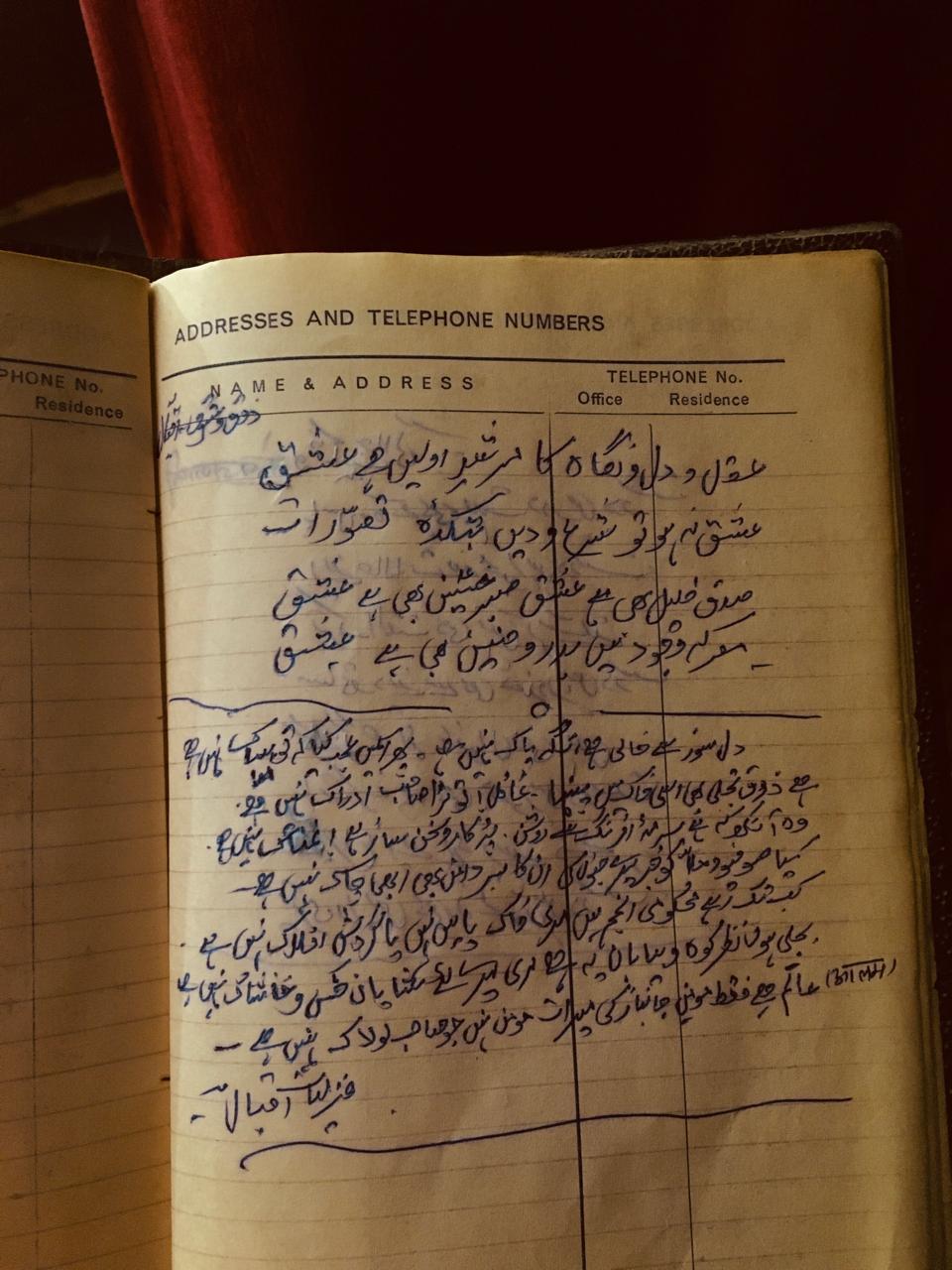

However, Maulvi Anis lives on. His passion has been inherited by generations now. Firstly, his daughters, with stacks of Pakeezah Aanchal and their father’s unrelenting love for reading, and re-reading. His daughter, Rehana Khatoon, my Phuphi, once said that books never get old, they become new each time you read them. They too, would sit in the chaupar, after a long day of work, reading Ibn-e-Safi or perhaps a story too scandalous from one of the zenana periodicals, laughing past compromises, living a fleeting moment of joy before the day burned low. Maulvi Anis lives on in his son, Dr. Aish Mohammed Khan. A man with ghazals written at the back of his telephone diaries. He had a small clinic on the corner of a street in Lucknow. Often silent. He’d sit through slow afternoons, fiddling on his swivel chair. By all accounts, he should have been sad. But he lived life with fierce joy. He would watch musharias late into the night. Years later, I found his telephone diaries, full with copious notes; poems, ghazals, songs from films. I remember one sher in particular;

In fizaon mein hai gunjaish-e-parwaaz bahut,

Ek baar jism ke zindaan se nikal kar toh dekho

In these winds, there is a promise of flight,

Just once, break free from the prison of the body and see.

And to me, this speaks of all that could have been—of lives never lived because the world couldn’t make enough space for simple dreams or this nasty thing called fate. But it speaks of mad hope, too. It is a testament. A dying man choosing not his land, or his baghs, or anything but his books. A battered doctor remembering poetry for no greater thing than mere joy. Women, behind the purdah, rushing to terraces or quiet rooms for nothing but stories. A Haji Dada turning into a madman for the world, but in his secluded, sodden room, he spilled through and across mortal borders, living all the lives he could in the little time he had.

This is my tribute to all those madmen in the forgotten corners of India, turning tides against their fate. Who will never be known, never be written about, and never seek to be. Who, to the world, will always be the subaltern—a nameless, faceless whole. Butthey do have names. They had lives—layered, complex, ugly and beautiful.

So here it is, in their name—a testament to those who lived, and read, and burned, and dreamed.

Dada’s books stacked in a taak near his palang

Badi Ammi with her Pakeezah Aanchal

Dada re-reading his books through an afternoon in January

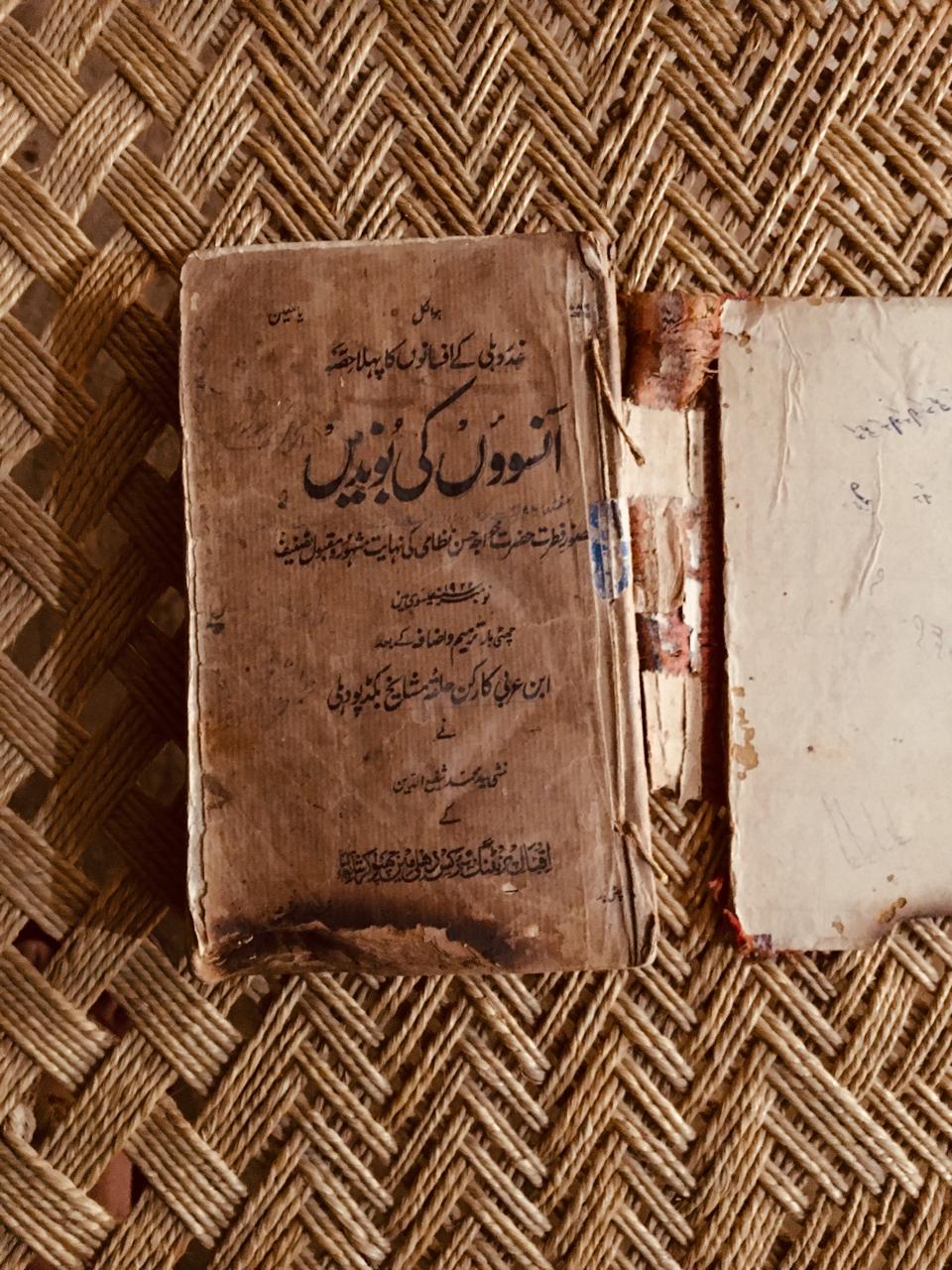

One of my Nana’s books, an avid shikari (hunter) and also a reader

Dada’s books found in his bakas after his death

Phuphi and his daughters revisiting their beloved copies of Pakeezah and Mahakta Aanchal

Phuphi, behind the camera for a documentary on her love for reading, Nigaah-e-Niswaan, co-directed by my sister and journalist Nuzhat Khan

Bade Papa’s telephone diary, with ghazals scribbled on the back

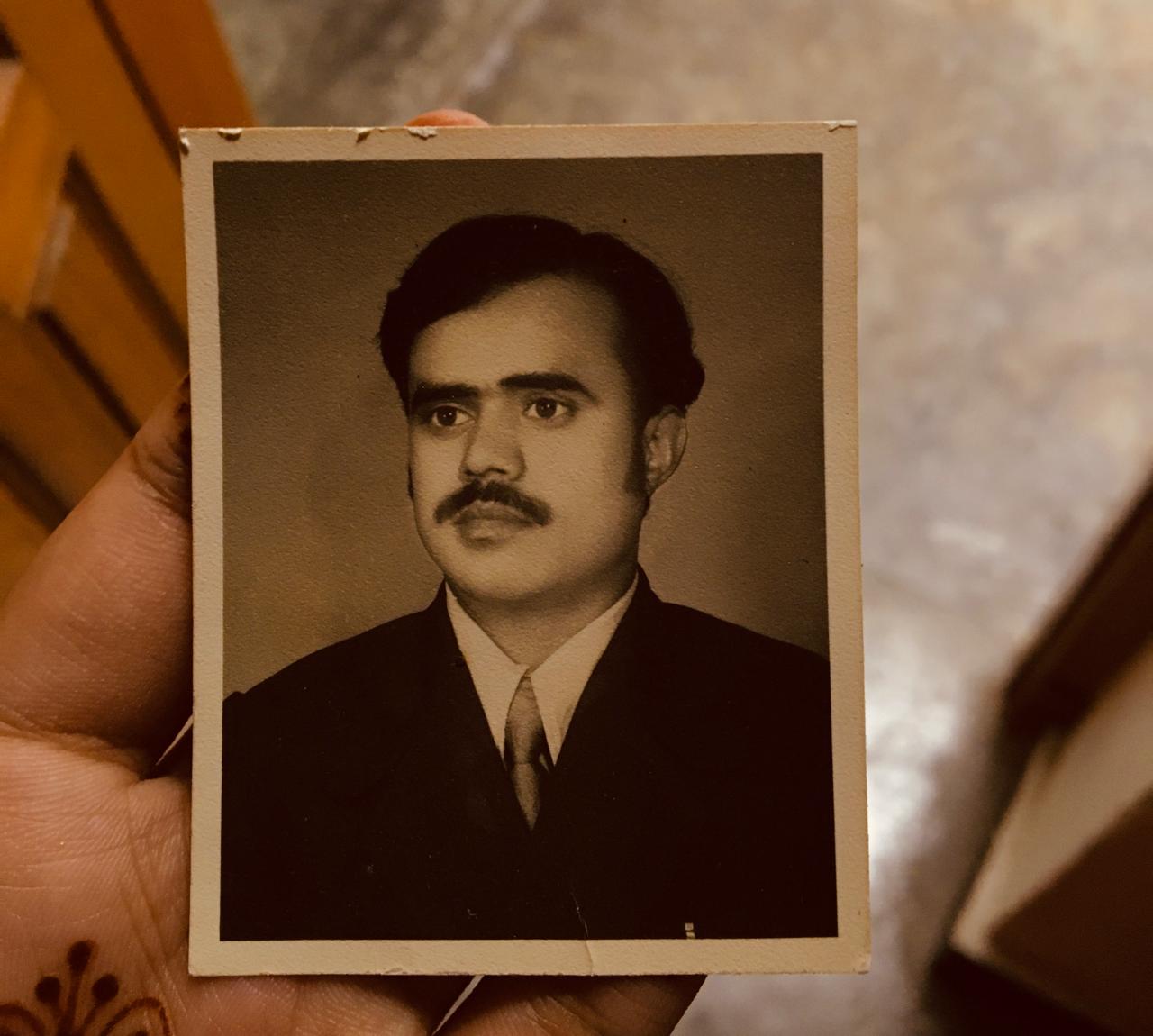

Bade Papa, Dr. Aish Mohammad Khan, always a poet at heart

Tasneem Khan is a writer from Lucknow.