With the Heart at the End/ Ajay Kumar/ Issue 17

i. Moolam

With buzzcuts and tucked-in formals the Pisakatans sneak past the senior-chettas grunting over the TT table. Through the back entrance, across the vagina pond, and all along the campus walls reeking of beer and piss, until they reach the Selaiyur gate. Once they come out of the campus limits, the Pisakatans regain their names: Joshua and Augustin. They look at each other, roll up their sleeves, tousle their hair, and laugh in relief.

Their plan for tonight is clear: Joshua will wait for Deepika. When he sees her in the distance he’ll start walking towards her with a broad smile. They’ll side-hug for now with hopes of front-hug on the way back. He’ll complement her dress—which is a peach top from Max and black jeans from Zudio— as they cross to the other side and wait at the Poondi Bazaar junction for a share-auto which will drop them at Camp Road. He’ll pay twenty, she’ll insist on paying her ten, but he’ll say, It’s okay, next time you pay, assuming and suggesting a next time. She’ll put her wallet back into her purse and tuck a lock of her hair behind her ear as they walk up to HiSide Bar slightly brushing against each other with slight apologies. While Joshua’s on his date Augustin will score a potlum from KK at the Railway Grounds so that they can smoke up together later at night. What wasn’t clear in the plan, at least to Augustin, was how at the sight of Deepika, Joshua would completely forget him, how she wouldn’t even acknowledge him with a nod, and how they’d cross the road right in front of him as if he didn’t exist.

What’s your name? A senior-chetta had asked him, on his first day of college, with the Anti-Ragging Cell poster rolled up like a baton in his hands.

Augustin, he’d replied.

What’s your name? The senior repeated, joined by other senior-annas.

Augustin Kumar.

What’s your name?

Augustin was silent.

Pisakatan. It means piece-of-shit in Pig Latin, the senior-chetta said.

No, it means piece-of-shit in Sangam Tamil, a senior-anna interjected.

That’s what you are, got it? The senior-chetta said. Now what’s your name?

It’s been three months since that day. Joshua had been standing right next to him, going through the same drill. A knot had bloomed between them, tying them together, as if they’d suddenly become the keepers of each other’s humiliation. Once they became roommates, they were inseparable, like a pair of balls in a nutsack called E22, right from Initiation all the way to Privilege. They were sent on their first Task together to KK Tea Corner on the other side of the railway station. Joshua was ordered to buy a Marlboro Doubleswitch while Augustin was told to get a single banana. If they didn’t return in ten minutes they’d be dunked in the vagina pond. They flew across the campus, jostled through the crowd on the railway bridge, and reached the stall in West Tambaram. KK didn’t ask them for money. Instead, he called the seniors and gave his approval. As they were running back, Joshua stopped on the way for a smoke. Augustin had panicked at how chill Joshua was. He could feel his throat getting constricted by exhaustion and smoke, could feel himself running out of breath just as he was running out of time. He’d ran, leaving Joshua behind, the single banana held aloft like a dick, like a flag, flashes of his father flitting in and out of his mind, plucking and unpeeling a ripe-enough banana for him from the bunch he’d be lugging to the market that dew-pissed morning, but the fear of being dunked in the cold dirty water jerked him out of it, into a faster run, up the stairs, past the crowds, back into the campus, meeting the seniors at the Warden’s Dick, right in front of their hostel. Joshua reached eventually, huffing and struggling, with the cigarette dampened by his sweat.

Augustin saw them pick Joshua up by his armpits and take him towards the pond which, at least to these hormone-heavy boy-men, resembled a vagina. Joshua felt tickled. He giggled and pedaled his feet in the air. He splashed into the cold water with a shrieking “Karthave!”. The water came up till his navel when he stood up and pushed away a plastic tube that clung to him like an umbilical cord. As he came out of the pond, dripping with water, removing the banana peel and the polythene bag that’d stuck to him, he saw the seniors send Augustin away. Joshua had narrated this to his classmates the next day and they all clicked their tongues in pity except Deepika who broke into laughter:

Vagina Pond? Warden’s Dick? When the fuck will you guys grow up?

In the share-auto Joshua notices that she’s put a bandaid just behind her ankles because her shoe bites into it. He puts his arm over her shoulder because there is no other place to keep it. At the bar, they get a half of Absolut Vodka and mix it with Nimbooz.

It’s been three months, Deepika says.

Let’s toast to that, Joshua raises his glass. Three months!

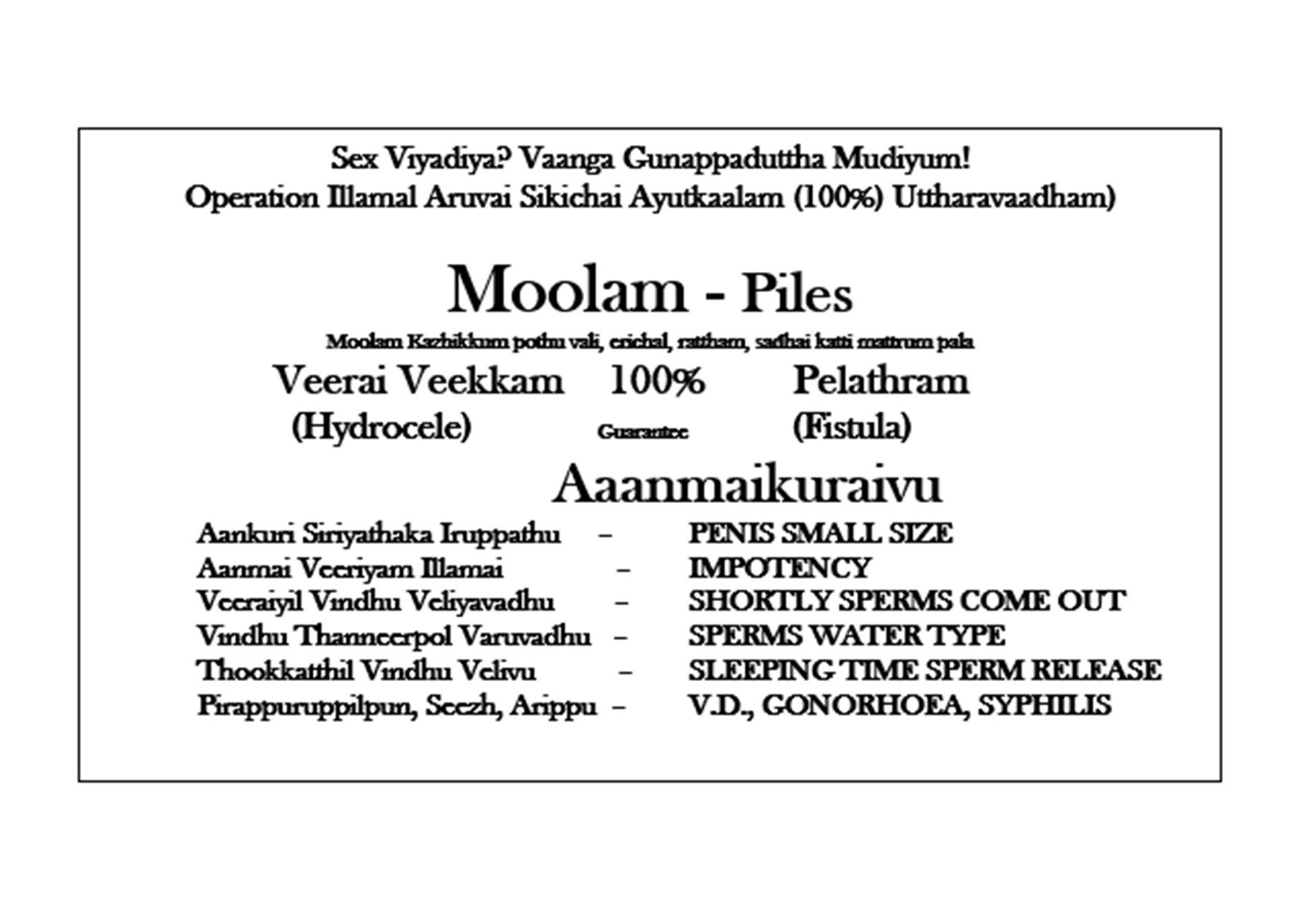

Three months, three months. As soon as Augustin sees them get into a share-auto he decides to cross. As he waits for the signal to turn red he notices a flyer stuck on the traffic-pole. His eyes read the “Piles” in English before they notice the “Moolam” in Tamil. A corner of the Moolam flyer has come unglued, flapping in the breeze, like a hand beckoning him as if it too thinks he’s a piece-of-shit. In these three months Augustin has learned that the vitiligous skin of Chennai is not, as it is usually believed, the glitzy posters, tall cut-outs, and dangerous hoardings of filmstars, politicians, and filmstar-politicians, who rise and fall, come and go, but it is these small flyers, in pink and yellow and blue and white, besides and under and over the other posters, the Stick-No-Bill walls, and the crowded bus-stops, everywhere and always and unchanging.

The red is in his eyes. He crosses. Walks to the end of the Railway Ground, steps onto a quiet dark road between the Railway Quarters and the last platform, and waits for KK. Another Moolam flyer on the ground with tyreprints all over it. As he is reading it

there’s a tap on his shoulders.

First score for yourself, huh? KK says, taking the money.

For Josh and me, Augustin replies, putting the potlum in his pocket.

Man only now, man, KK says, leaving.

He didn’t think it’ll be over so quickly. The weight of the potlum in his shirt-pocket begins to take root in his heart. When he takes it out and slips it into his pant-pocket the weight begins to creep towards his belly. He doesn’t want to stay here but he doesn’t want to go back either. If Joshua’s date is going well he’ll probably be late. He checks BookMyShow and finds that Vaazhai is playing at National Theatre at 7 PM. It’s almost houseful but he manages to get a ticket for a front row seat. Earphones in. Plays Arivu’s latest album. Strides past the shady piss-reeking area just behind the Tambaram East bus stop. Past the bottles of Kingfisher Strong corked with its own labels, empty quarters of SNJ 10000 and Anaconda No.1, a shattered half of Mansion House. Past the Railway Union’s autorickshaw stand, a bewildered Marx and a proud Lenin on their notice board, behind which an autokaaran is eating brinji rice on the backseat of his rickshaw whose windscreen has pictures of the filmstar Ajith and the boy-god Murugan side by side. Up onto the footpath. Up onto the escalator. From East to West. Then right onto the foot overbridge. Past a man with elephant’s foot plucking his rotten toenail. Past an old woman on a day-old Dinathanthi with coins clanging in her begging bowl. At the intersection, there are two transwomen clapping. He takes off his earphones, just to hear what they’re saying, even though he knows they’ll ask for money and he’ll say no and hurry past, and they do ask for money and he does say no but he doesn’t hurry past. He turns around and looks at them. He finds them beautiful, in matching saris, a style his grandmother would wear but his mother wouldn’t: a glossy light blue shot through with a tinge of green, like a jungle blending into the sky. Down the escalator. The other side gets overloaded and comes to a halt. A woman, with her head on the handrest, is dragged above by the people. He gets down. Periyar Nagar, a board announces. This is the West of Tambaram, the other shore of Chennai, without the beaches or the memorials, filled with people who only relate to the city in transactions and in transit. He sees Ambedkar’s statue, inside a golden cage, the index finger of his arm pointing ahead. He’d posted a Reel of it once on Instagram. The shot lingered on the caged statue with the chaos in the background, slowly zoomed in till the edges of the cage became the edges of the screen, slow-panned in the direction of his finger, revealed the national flag, half-hidden by the bridge he just crossed, zooming again, until the saffron and the green go out of the frame and only the blue wheel of dhamma remained. The caption said: They’ll paint the blue cage golden. And it’d gone viral, which meant very soon he started getting flooded with comments like

Here, take my *chair emoji*

Dalit this post *skull emoji*

Jai Bhim

Jai Chutki

Jai Dholu Bholu

Jai Raju Jai Jaggu

Jai Tuntun Mausi ke Laddu

after which he’d turned his account private. He looks at the flag, flaccid now on this windless night. Clicks a picture. Walks towards the Post Office, through the bus stand, and enters Rajaji Road.

ii. Pu Ja Tho Zha

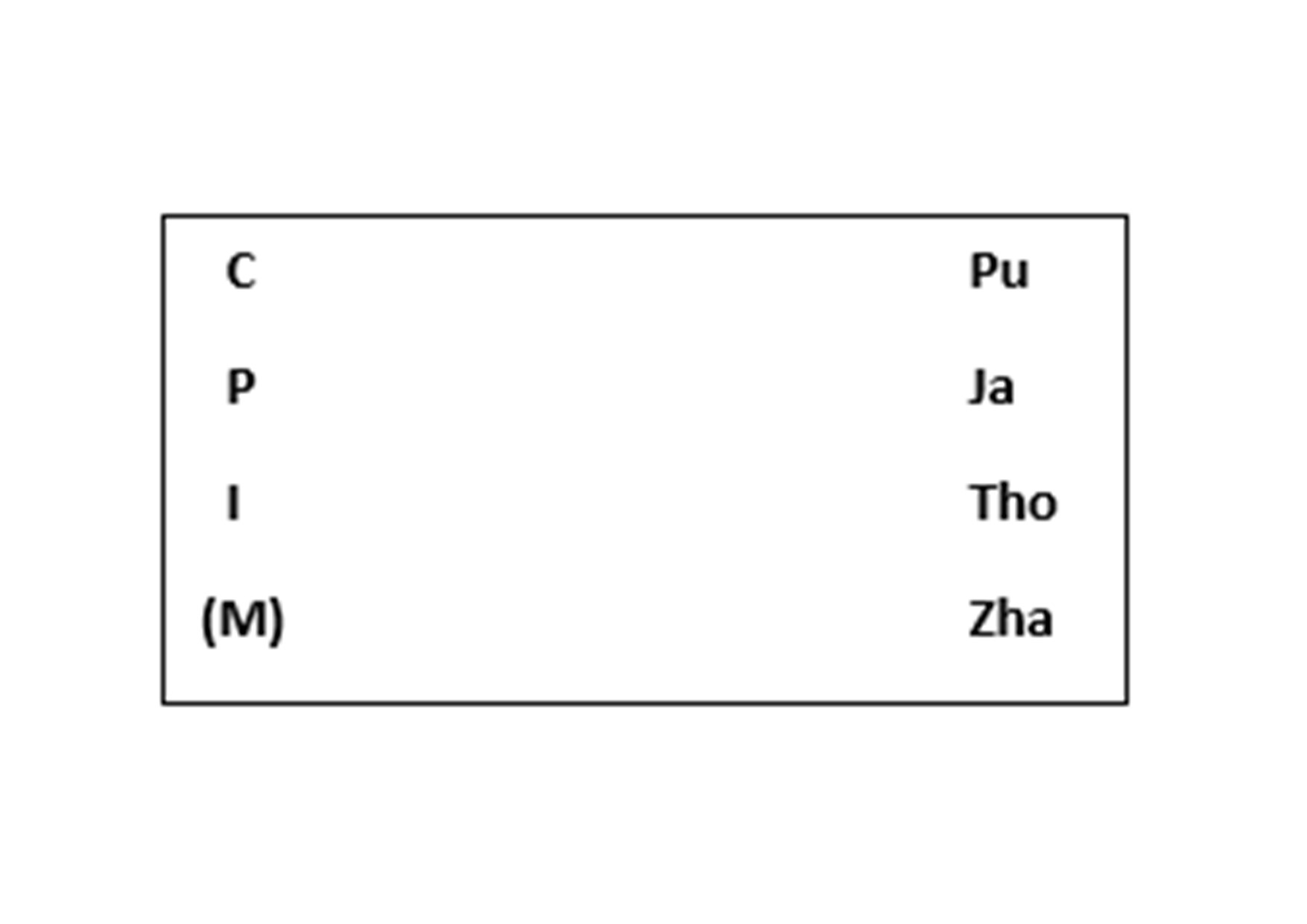

Augustin sees I look at his watch, waiting for his parcel of 100% halal beef pakoda from the roadside cart. M is waiting at a distance, telling I to hurry. He walks on. Today is Vijayakanth’s birth anniversary and the street is lined with his party’s flags: red and black with a flaming torch in the yellow middle. Scattered among them are the flags of the Communist Party, which is holding a conference against the recently passed criminal bills at the TGP Mandapam. He looks at the flag

but doesn’t understand what the Pu Ja Tho Zha stands for. He googles but google doesn’t know enough Tamil yet. He feels inadequate, as if he’s losing touch, as if he never had any touch, with his own language. At the next intersection, I and M meet the others. T keeps the parcel on a window-ledge. The man wearing the Heart costume is the last one to join. Together, they form ‘I Heart TAMBARAM’, and sway to the theme song of the multilevel shopping complex being inaugurated. Some politician in white-and-white cuts the ribbon. Despite his repulsion, Augustin finds himself humming the song as he enters the theatre compound. Packed house. 700+ people in that single-screen. Reaches his seat just in time. Bits of oral-cancer infected mouths have been dropped into glasses of water. Black pus has been squeezed out of sponge-like lungs. And the movie begins.

When the name of the film is being scribbled across a bird’s-eye view of a banana plantation, all the phones go up in the air, trying to capture the moment for a Snap, an Insta Story, or a WhatsApp Status, and to Augustin each screen looks like a little cigarette box on top of a pile of banana leaves. He remembers how it was during the Ockhi cyclone that he wrote his first poem. When he saw a banana plant being thrashed by the torrents but how still and ready it seemed, as if being uprooted was a part of its growth. He’d started it in Tamil, imitating nature verses from his textbook, but it finished in English. “Perspective,” it was titled. Sometimes he thinks he began writing in a strange language so that only strangers could read him. Now that he’s joined his BA in English Literature, there seems to be no way back. He must’ve been around the same age as the child-protagonist in the film when he wrote it. The protagonist is forced to lug bananas, something he hates with his guts, something he will go to any extent to avoid. His neck hurts. Augustin’s neck begins hurting, straining to peer up at the screen from his front row seat. Flashes of his father invade him again as goes to the toilet during the intermission. A large vein between his father’s half-bald head and his dark, always-oiled neck, like a snake lodged inside his body. He opens his zip but he cannot piss. There are no dividers. There are people waiting behind him for their chance. He cannot piss. He goes back without pissing. During the entire second half he shivers in the AC with a full bladder. During the climactic stretch, where the brutality of loss and hunger overwhelms everyone, a young couple behind him giggle and murmur. The smell of their caramel popcorn makes him want to retch. He wants to stand up and thrash them but he feels that if he moves even a single inch he’ll piss his pants. He was pissing at his usual spot that evening, between the banana and the tapioca, when he heard his father and his mother yell at each other, right in front of their house, just before the river channel. His father had come dead-drunk again. Ockhi had ruined them. The half-acre that his New Convert Great Grandfather had bought and his Union Leader Grandfather had built a house on was completely flattened. Only a few Nairs with vast estates managed to scrape by. His father began tapping rubber at the neighboring Thampi’s plantation. He had to wake up around 3 in the night and finish tapping by dawn. Then on somedays he’d lug bananas, two or three bunches at a time on a towel warped into a disc on his balding head, to the tempo waiting near Moolachel Church, which would take it to Thuckalay or Monday Market. He’d often come back drunk and his mother would massage his neck with kayathirumeni oil while yelling at him. The black ash on her fingers, residues from the coal-roasted cashew shells she crushed on a per-load contract, would mix into the oil, turning his neck even darker. But that evening was different. His mother had come in and shut the door. He went out and saw his father stagger on the banks of the channel. In the failing light he could only see a silhouette of his father, his hands raised above his head, as if he’s wearing a crown, or carrying a load, before he hears him splash into the water. He yells for his father, then for his mother. His mother yells for Thampi who runs to the next washing slope and extends a coconut stalk which his father grabs hold of and climbs back up. His mother slaps him and tells him to drag his father back home. The boy’s mother smashes a plate full of rice onto her head in guilt. People start walking out as the credits roll over an oppari song. He goes back to the toilet. No dividers. As if the insides of his body have been turned upside down he falls to his knees. Nobody picks him up.

iii. Vaazhai

He comes out of the theatre into a soft rain. He remembers the last lines of his first poem: “When the tiny droplets bounce off My leaves / The Joy I get never seems to cease.” He thinks if he walks long enough in the rain nobody will know that he has wet himself. He walks. Just outside the theatre compound he sees the human billboards, without their costumes, tired but laughing, drinking Madurai-special jigarthanda with agar jelly. Their costumes are kept aside, between the narrow road and the nonexistent footpath, spelling out ‘BAR IT MAMA’ with the Heart at the end. For some reason, this fills him with a consciousness of the time. He wonders if he’s late, if Joshua is already there and waiting for him. He runs, through the rain, flashes of his father flit in and out of his mind, but the fear of leaving Joshua waiting jerks him out of it, into a sprint, up the stairs, through the crowd, but he collides with a stranger, and the potlum falls out of his pocket. He grabs it back. Looks around. Nobody noticed. Beach Local is arriving on Platform 5. He walks past them, down the stairs, back into the campus, and calls Joshua. He hasn’t reached yet. He’s on his way, he says. Augustin waits.

As he waits, his breath finally returning to its rhythm, he wonders what he hopes for. He’ll be happy for Josh if it goes well. She’s nice and they look good together. But that’ll also confirm his belief that only beautiful people get beautiful people while everyone else will have to squeeze out compromises and repress their resentments. He cannot imagine a future where he is not alone. Not strong enough to seek love, not weak enough to accept a marriage based on caste and constellations. If Deepika had said no, he’d have more time with Josh, but that might also break his heart and suck the joy out of him, which is what he loves about him. Joshua is silent when he returns, his eyes downturned. Augustin guesses that it didn’t go well.

It’s okay. I got the stuff. Let’s just go smoke up, he says, not startled at the relief flooding him.

They reach E22. Begin crushing. Add a bit of tobe. Augustin opens his mouth to tell him about the film when Joshua whispers:

It went well. She said she likes me too. Augustin doesn’t stop crushing, just looks up from it. We’re going for a movie tomorrow. Vaazhai. It’ll be fun.

Joshua rolls. It’s a fatty. He taps the filter on the Bible lying next to him. He lights it. He takes the first puff. He lets smoke out of his nose. He passes it to Augustin. They both get high and things begin to start looping. Joshua passes out on the bed, drifts into sleep with a mumbling smile on his face. Augustin remembers. When Joshua came out of the pond, dripping with water, removing the banana peel and the polythene bag that’d stuck to him, the seniors had sent him away on another task. He’d to walk up to the Chairman’s room with the banana balanced on his head. His neck was hurting by the time he knocked at the door and it opened to reveal eyes high and hooked to the screen. He couldn’t breathe in all that green haze and laughter. He’d come back in a fit of cough. Joshua was already asleep. Joshua is sleeping. The room is hazy. Joshua rolls over. Augustin steps out for a breath but keeps going. Past the seniors playing TT, through the back entrance, all the way to the lip of the pond. He jumps. The water comes up till his heart when he stands up in it. He shivers in the cold. The fog swivels around him. He dunks himself and opens his eyes under the water. He feels he can see himself reflected on the dirty tiles. He likes that his eyes look red in it.

Ajay Kumar is the author of the chapbook balancing acts (Yavanika Press, 2023). His stories have appeared in The Masters Review, SAND, and Muse India, among others. He received the Srinivas Rayaprol Poetry Prize in 2024 and was longlisted for the Toto Funds the Arts Award in 2023. He lives in Chennai.